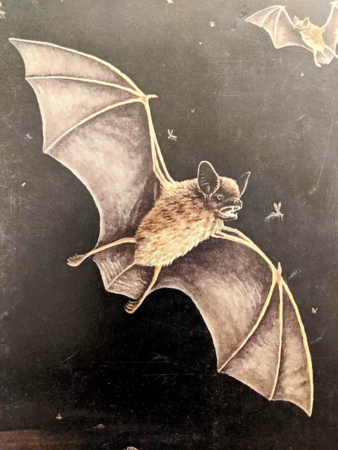

I remember a few years ago; the Pennsylvania Game Commission asked me to produce a cover featuring bats for their Game News magazine. As a wildlife artist, I enjoy painting all kinds of wildlife, but I’ll admit that bats were not on my list of things to do; after all, who would ever want a picture of a bat hanging in their house? I actually really liked the painting when I got it done, and so did my wife.

Surprisingly it was grabbed up in a very short time by a local woman, and several more expressed an interest in it.

It’s no secret that a lot of people don’t like bats, especially when they are flying around your head in the dark. The truth is; however they are a very beneficial creature to have in your neighborhood; no, not in your house but somewhere outside your house. Why so beneficial? Well, your average little brown bat is capable of devouring in excess of 600 mosquitoes and similar-sized insects per hour. A lack of bats means more mosquitoes and other annoying insects, and I, along with many other people, have encountered that problem when going out at night. Even in the daytime, entering wooded areas and thick vegetation results in constant swatting at humming insects, most of which enjoy feasting on us.

I was elated one day last week when I walked out in the backyard at just about dark, and there were two bats flitting about; the first time I’ve spotted bats in my area in almost two years. As many are already aware, our state’s bat population has been seriously declining, with the vast majority of our bats disappearing. The reason for the loss of bats is attributed to a fungus known as white-nose syndrome.

White-nose syndrome first showed up in New York around 2006. The fungus colonizes on the skin around the muzzle, ears, and wings of the bats, which forces them out of hibernation into the cold winter nights where there are no insects available, and the energy used after being forced out of hibernation cannot be replaced. The bats die of malnutrition and exposure.

There may be some good news on the horizon, however. The Game Commission and other biologists have found that a slightly lower temperature where bats hibernate gives bats a better chance to combat the fungus. Biologists have found that a mere decrease of 2.5 degrees in temperature in caves where some bats hibernate greatly increases their chances of successfully completing hibernation. When you consider that cave bats only give birth to one pup each year, that’s not likely to result in a quick recovery, but it is a positive sign.

Former mine sites often serve as bat hibernation locations, and it has been found that mines that were excavated into a hillside at a greater slope than the relatively flat excavation offer a slightly cooler temperature. It was also found that adding a ventilation hole to the shaft pulls more cold air in, dropping the temperature below the 50-degree mark and improving the chances of successful hibernation. One such ventilation hole was added to a mine in Blair County and bat numbers over a few years increased from 26 little brown bats hibernating to 82.

Of course, there is much more work to be done, especially since not all bats hibernate in caves and mine shafts; in fact, it’s not actually known where some bats do hibernate. In the meantime, I look forward to seeing more bats outside my house and fewer mosquitoes.