The more I got into strength training as a kid, the more I became fascinated with its rich history. Strength and fitness knowledge, in general, wasn’t always accessible to the general public. Up until the early part of the twentieth century, it was reserved for billionaires and royalty. Early trainers were sometimes regarded as equal to physicians. They had only a single VIP client at the highest levels before the internet was flooded with workouts, pictures, and videos — knowledge of what was known then as physical culture was considered sacred and closely guarded.

It wasn’t always bench presses and biceps. In fact, in the early days, those exercises did not even exist, and when they did come into being much later on, were considered exercises for the vain and lazy. (I’m just stating facts, I actually thoroughly enjoy those exercises.) Early fitness training was not so clearly organized into sets, repetitions, and systems. Enthusiasts and professional trainers basically practiced exercise like a skill and used intuition to tell them how hard and long to push themselves. Some trained heavy and some trained light, but all serious students of strength and health of the day regarded the bent press to be one of the gold standards of strength.

According to Harold Ansorge, circa 1943, the bent press was a “lift of supports,” meaning it was a slow, steady lift that excluded speed and momentum. Unlike the explosive Olympic lifts of the clean-and-jerk and the barbell snatch, the bent press was a steady progression of movements until the weight; usually a barbell, sat in its final position overhead. The idea was to develop ligament and tendon strength and to train the largest muscle groups of the hips and back to lift heavy objects. Basically, the bent press was the foundation on which rested all other strength training exercises.

The lift can be broken up into three main movements:

– Lifting the weight to the shoulder.

– Initiating the press from the shoulder.

– Rising from the squat position once the arm is straight under the weight.

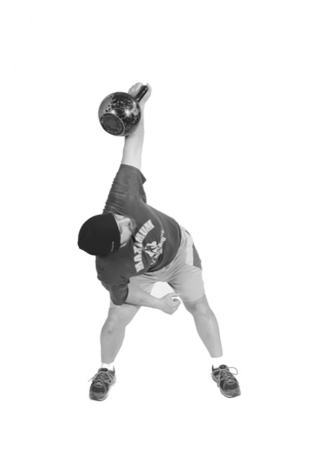

Think of a one-handed shoulder press overhead where you must simultaneously lean to one side, drop into a squatting position, and lock out the pressing arm. Now picture all of that with a full-length barbell that might weigh hundreds of pounds and wants to spin out of your hand. It sounds difficult and complicated because it is. This is also probably one of the reasons it is not practiced much today. That, and the fact that it is difficult to show off your bent press but easy to flex your biceps.

Early strongmen were routinely capable of lifting well over their own body weight with one arm. All-time great Arthur Saxon held the record of the day with a lift of 336 pounds at a bodyweight of 210 pounds, and Robert Hoffman, of the famed York Barbell, was capable of bent pressing 285 pounds at a bodyweight of 259 pounds which made him a giant in those early days. Another all-time great was Thomas Inch, whose world-renowned giant Inch Dumbbell is considered a standard for grip strength enthusiasts. Inch was able to bent press 300 pounds, also at the bodyweight of 210, respectively.

The bent press is great for developing strength, flexibility, and balance in your midsection hips and back, though it takes great concentration and needs to be performed very slowly. In addition, repetition ranges of 3 to 5 per set work well. Most importantly, consult with your physician should you decide to incorporate the bent press into your routine and get training from a fitness progressional that is versed in this old-school exercise. To begin, the weight should always be lined up with the center of your base of support. This is the point directly between your feet. Also, to help you maintain proper body alignment, your eyes should never leave the weight. If using a barbell, tip the weight on its end and rock the weight to your shoulder. If using a dumbbell or kettlebell, clean the weight to your shoulder. Turn the foot on the opposite side of the weight outward and slowly lean away from the weight. As you lean away from the weight, relax your hips and beginning squatting down. As you are squatting, push the weight away from your body, all the while keeping it over your center of mass for balance. As you lean into the bottom position, lock your arm out. Once the arm is locked, you can begin to rise into a standing position to complete the lift, holding the weight straight overhead.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *